Pasture Management for Breeding Waders at CAFRE

Since 2009, CAFRE through the Glenwherry Hills Regeneration Project (GHRP) has developed management at the CAFRE Hill Farm for breeding waders through a combination of technologies including, pasture management for breeding waders, provision of scrapes & multiple water sources and predator control. This has been targeted across a wider landscape scale with the 960ha hill farm as the focal point of a wider 3000ha GHRP predator control area.

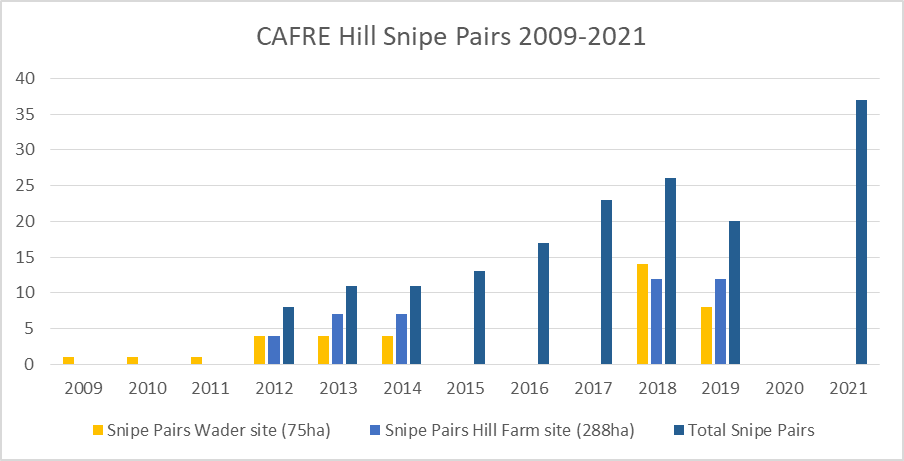

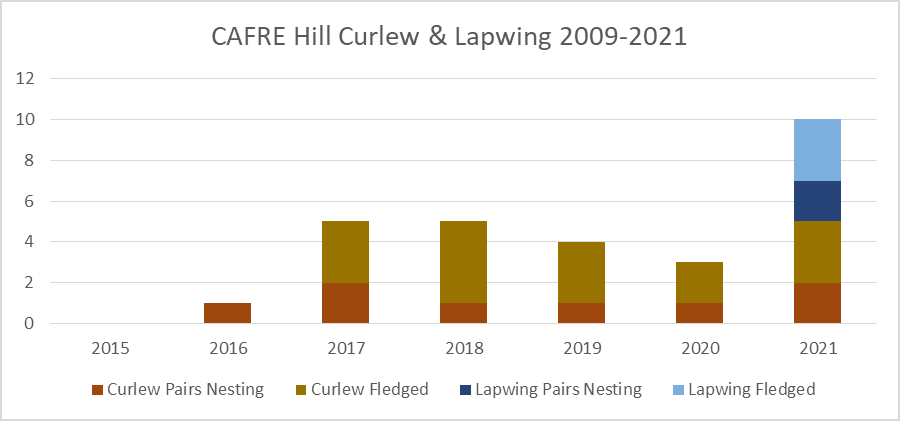

The high level multi-faceted management regime has been effective at increasing the pairs of breeding waders from approximately 5 in 2009 to over 40 by 2021. The site holds the most successful (productivity) Curlew pair in Ireland over the past 5 years.

Further project development in winter 2021 to improve sward structure and invertebrate provision for wader nesting & rearing through cattle grazing has successfully incorporated out wintering (Nov-Feb) of excess condition suckler cows on the Vogie 70ha breeding wader site to replace previously required mechanical flailing operations.

Due to the specific needs of breeding waders (eg. snipe, curlew, lapwing) modern standard agricultural pasture management is less likely to achieve successful fledgling outcomes and therefore long term population increases than a programme of modified pasture management.

Site optimum requirements for waders vary slightly between species but positive management practices included in Agri-Environment Higher level schemes are summarised as;

- Active late summer & winter grazing, ideally with cattle at some point to achieve mixed short swards, with some tussocks or light rush cover which has been grazed out by mid-April.

- Reduced stocking rate (<0.75LU/ha) or no stock during the nesting & rearing season (between mid-April – end of June)

- Restricting management so that; No mechanised field operations occur between April–end of June. No fertiliser applications occur between February – end of June. No pesticide, cultivations, reseeding, or drainage works occur within the site.

Active control of rush, scrub, tree occurs between July & March including a restriction on hedge planting.

Background and problem

Since 1960 there have been considerable population declines and range contractions in breeding waders such as Curlew, Snipe and Lapwing across much of western Europe. Declines have been attributed to land drainage, intensification of arable and grassland farming, afforestation and increased predation.

Northern Ireland has historically supported important populations of breeding waders due to high annual rainfall and saturated gley/peat soils with damp grasslands, species-rich pastures, swamp, fen, and extensive peatlands providing key breeding habitats for Lapwing, Snipe and Curlew respectively. In 1987, Curlew and Snipe populations in Northern Ireland were estimated to represent 10% and 14% respectively of the Britain and Ireland population. The survey estimated a 66% decline in lapwing across Northern Ireland. Curlew showed a 58% decline. (1) (2)

Waders are unusual in that the chicks have to feed themselves from day one. This feature requires soft pasture with a provision of soil invertebrates, short grass which enables young chicks to move across the site and also a mixed structure of tussocks to provide cover as risk of predation is extremely high due to an imbalance of meso-predators. These conditions would have been common in the past in Irish grazed meadows before drainage and intensive fertiliser & pesticide use. Breeding wader pasture management practices provides the most optimum semi-natural grassland habitat however additional technologies of water table management, provision of open water sources and predator control are also required to reverse population declines. These will be addressed in later technology investigation reports.

Current industry uptake of the breeding wader pasture management protocol

117 farmers have a total of 2024 ha’s in the Breeding Wader Option of the EFS Higher scheme @22/1/22.

Evidence for the success of using the pasture management for breeding waders.

European research predominantly from the UK & Netherlands identifies the likely cause of breeding wader low productivity as the combination of changed agricultural practices and predation.

- earlier cropping, mowing, and grazing dates with agricultural intensification and climate change (2) resulting in destruction of eggs and chicks by agricultural machinery and livestock (3)

- reduced food quality (invertebrates) and/or availability in intensively managed grassland monocultures or as a result of large-scale drainage, resulting in poorer chick growth and/or survival (4)

- increased predation of eggs and chicks due to high predator densities, combined with greater susceptibility to predation in degraded breeding habitat (5)

A 2018 wide ranging review of European data identifies positive outcomes for wader population trends and productivity associated with the use of Agri-Environment Schemes, where breeding wader management was specifically targeted. (1)

The review identified that grazing sites benefits several wader species, likely by creating and maintaining a more heterogeneous and less dense sward structure and composition preferred for nesting and foraging.

However, grazing within the nesting & rearing period, even light grazing may lead to significant nest mortality through trampling, depending upon the livestock involved, or alter vegetation structure thereby increasing nest predation. (6)

Nest mortality can be reduced by either grazing prior to and after the nesting period or dramatically reducing stocking density.(7)

Organic farming can increase breeding wader abundance (8) and reductions in agrochemical use are broadly associated with higher wader abundance and occupancy (1) potentially due to an increase in invertebrate abundance. (9)

Wet conditions can provide critical foraging habitat with high food availability for both adults and chicks, particularly later in the breeding season when the water table is lower. Research reviews indicate that improved wet conditions can support greater numbers and higher occupancy of waders and can also benefit productivity, (1)

Whilst conservation measures have been shown to be more successful at achieving positive outcomes than expected by chance, wader populations continue to decline. (1)

As small successful sites are more vulnerable to climate and predation impact the restoration of sustainable wader populations in the wider countryside may depend on the implementation of effective measures at a much greater scale. (10)(11)

Demonstration at CAFRE

REFERENCES: Background & problem

- Partridge & Smith 1992: Irish Birds 4: 497-518

- DAERA Breeding Waders scientific evidence for option. DA1/15/3085

Supporting Data Sources

(a) Ausden, M. et al. (2009) Predation of breeding waders on lowland wet grassland – is it a problem? British Wildlife 21, 29-38. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/251176/Wild_birds_1970-2012_UK_FINAL.pdf

(b) Henderson, I.G., Wilson, A.M., Steele, D. & Vickery, J.A. 2002. Population estimates, trends and habitat associations of breeding Lapwing Vanellus vanellus, Curlew Numenius arquata and Snipe Gallinago gallinago in Northern Ireland. Bird Study 49: 17-25.http://www.bto.org/sites/default/files/u31/downloads/details/breedingwadersnorthernireland.pdf

(c) WET GRASSLAND PRACTICAL MANUAL: BREEDING WADERS. RSPB 2005 http://www.rspb.org.uk/Images/wetgrasslandmanual_tcm9-132779.pdf

(d) Breeding waders Species Recovery Programme 2014 http://www.naturalengland.org.uk/ourwork/conservation/biodiversity/englands/breedingwaders.aspx

(e) SMART et al, Grassland-breeding waders: identifying key habitat requirements for management 2006 Journal of Applied Ecology Volume 43, Issue 3, pages 454–463, DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2006.01166.x http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2006.01166.x/full

(f) Lough Neagh Wetlands Breeding Wader (Redshank, Curlew and Lapwing) Species Action Plan 2008 – 2013 Breeding Waders in the Lough Neagh Wetlands

(g) BTO Research Report 365 Changes in lowland wet grassland breeding wader number: the influence of site. Report to Defra, RSPB & English Nature 2005 British Trust for Ornithology, ISBN 1-904870-17-1

REFERENCES; Evidence for the success of using the pasture management for breeding waders

(1) Franks et al, Evaluating the effectiveness of conservation measures for European grassland-breeding waders. Ecology & Evolution 2018 https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.4532

(2) Kleijn et al (2010). Adverse effects of agricultural intensification and climate change on breeding habitat quality of Black-tailed Godwits Limosa l. limosa in the Netherlands. Ibis, 152, 475– 486. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-919X.2010.01025.x

(3) Kruk et al (1997). Survival of black-tailed godwit chicks Limosa limosa in intensively exploited grassland areas in The Netherlands. Biological Conservation, 80, 127– 133. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(96)00131-0

(4) Kentie et al (2013). Intensified agricultural use of grasslands reduces growth and survival of precocial shorebird chicks. Journal of Applied Ecology, 50, 243– 251. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12028

(5) Bolton et al. (2007). The impact of predator control on lapwing Vanellus vanellus breeding success on wet grassland nature reserves. Journal of Applied Ecology, 44, 534– 544. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2007.01288.x

(6) Mandema et al (2013). Livestock grazing and trampling of birds’ nests: An experiment using artificial nests. Journal of Coastal Conservation, 17, 409– 416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11852-013-0239-2

(7) Pakanen, et al. (2016). Grazed wet meadows are sink habitats for the southern dunlin (Calidris alpina schinzii) due to nest trampling by cattle. Ecology and Evolution, 6, 7176– 7187. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.2369

(8) Henderson, et al (2012). Effects of the proportion and spatial arrangement of un-cropped land on breeding bird abundance in arable rotations. Journal of Applied Ecology, 49, 883– 891. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2012.02166.x

(9) Boatman, et al (2004). Evidence for the indirect effects of pesticides on farmland birds. Ibis, 146, 131– 143. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-919X.2004.00347.x

(10) Vickery, J. A., & Tayleur, C. (2018). Stemming the decline of farmland birds: The need for interventions and evaluations at a large scale. Animal Conservation, 21, 195– 196. https://doi.org/10.1111/acv.12425

(10) Walker, et al (2018). Effects of higher-tier agri-environment scheme on the abundance of priority farmland birds. Animal Conservation, 21, 183– 192. https://doi.org/10.1111/acv.12386